Like many of the leading early Hollywood Jewish film executives, the Wilshire Boulevard Temple was born out east, headed west, and Anglicized its name. The resulting palatial new house of worship represented a move towards assimilation that paralleled the desires and efforts of many of the Jews of the era shaping the American entertainment industry.

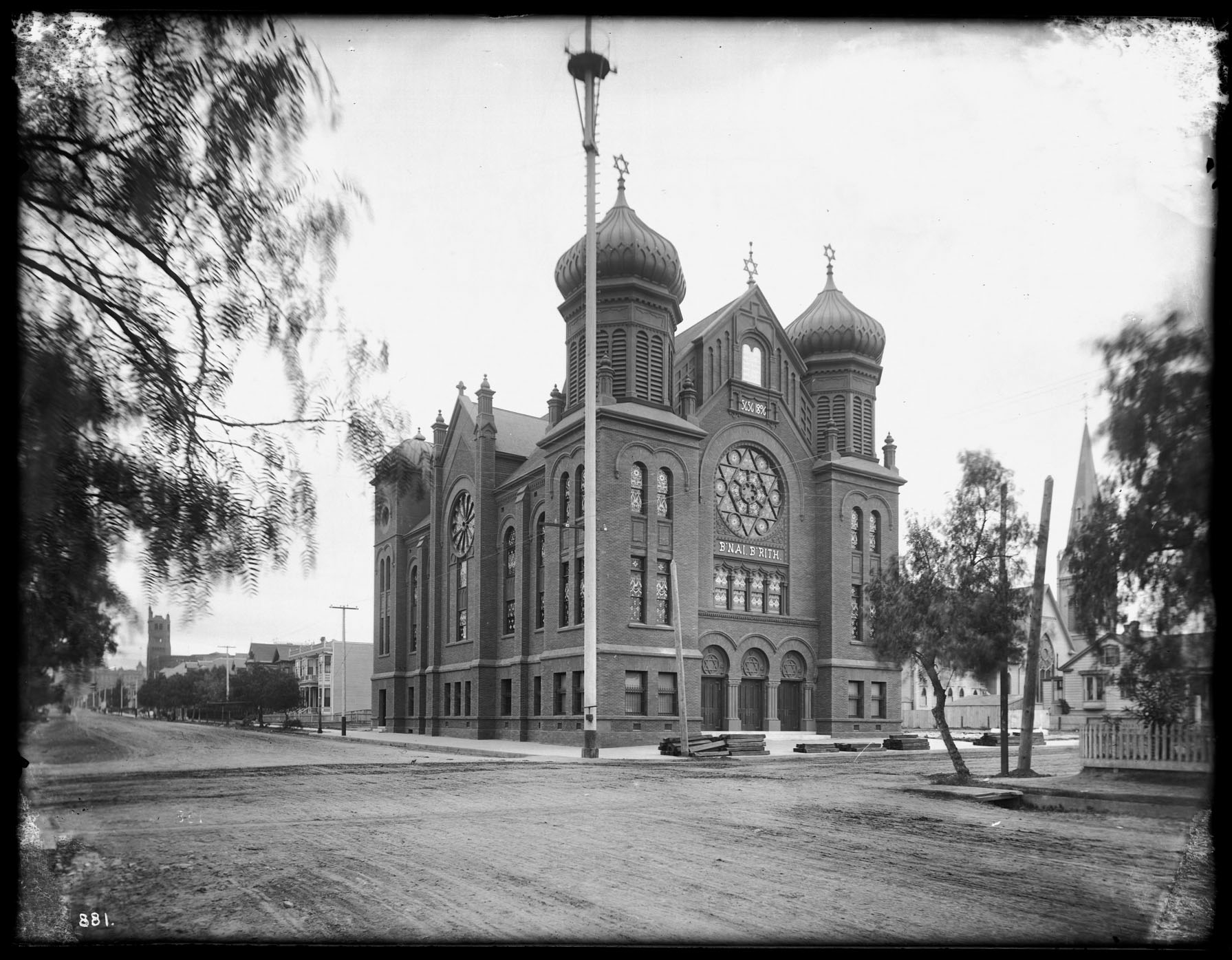

The congregation first opened during the Civil War era in Downtown Los Angeles, and was originally known as B'nai B'rith. When Edgar Magnin became head rabbi in 1915, his key initiative became creating a grand new home. Wilshire Boulevard Temple opened in 1929 as the cultural and spiritual home for a new generation of successful Americans, and a potent statement and symbol to the rest of Los Angeles—and their old-world forebears—that these machers had arrived.

Located at 3663 Wilshire Boulevard in what is today Los Angeles’s Koreatown neighborhood, this reform Judaism synagogue was, at the time of its construction, in the city’s modern, westside, car-centric area amidst posh private residences and other well-appointed houses of worship.

Architect A. M. Adelman was charged with creating a structure inspired by the famous cathedrals of Europe. He and colleagues spent $1.4 million ($18 million today) to construct the temple in a neo-Byzantine and Romanesque style, including its signature 125-foot-tall dome.

The bonds between the leaders of the film industry and the synagogue were deep. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer boss Louis B. Mayer was so close to Magnin that the studio head offered the rabbi a job, according to author Neal Gabler’s book An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood. Gabler recounts how Mayer and Magnin “lunched together two or three times a week, and they and their wives often attended previews of MGM films together.”

Hollywood’s power players helped make sure the temple’s Pantheon-inspired interior was memorable. Irving Thalberg (MGM) paid for the painting of an important prayer—the Shema for those in the know. Carl Laemmle (Universal) gave bronze chandeliers. Exhibitor Sid Grauman, a chandelier in the shape of the Star of David. Mayer, stained-glass windows. And Harry, Jack, and Abe Warner (Warner Bros.) sent their art director, Hugo Ballin, to paint murals showing thousands of years of Jewish history (Ballin later painted similarly renowned murals at LA’s Griffith Observatory).

Other film industry flourishes and techniques are evident: What appear to be marble columns are scene-painted to look that way. Also, many religious sanctuaries have walkways down the middle. Wilshire Boulevard Temple does not. Why? “Because these guys built movie theaters. There's never a center aisle in a movie theater either—it's where the best seats are,” the congregation’s rabbi told NPR in 2014.

Wilshire Boulevard Temple remains a prominent house of worship, with a membership in the thousands. The building is a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 2013, architect Brenda Levin completed a $47 million renovation. In 2022, the congregation opened an attention-grabbing 55,000-square-foot event space next door, built by OMA, the firm of famed Dutch urbanist and architect Rem Koolhaas.